Hackney Marsh 1 2 & 3

Foraging on the Commons of the past, present and future.

To walk across the Cow bridge, over the river Lea with its jostle of narrowboats, past the trees and bushes is to enter an explosion of space that is Hackney marsh. Some 300 acres of protected Commons. The flat marsh grassland has the feeling of being unpeopled, of belonging to nature. But within its history is a chain of role reversals that unravel in this global age and produce new directions for the Commons land.

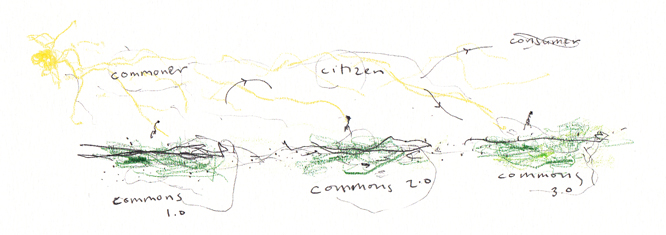

Early in London's history this was a proper marsh, flooded at will by the river Lea. Then it was drained and the land became usable as grazing pasture that commoners had rights of access to. The arrangement known as Lammas rights meant that for most of the year - other than the summer hay making season - commoners could bring their livestock to graze, collect firewood, coppice, forage, etc. Today's Cow Bridge, newly encased in lime-green for the London Olympics, is so called because it was over this bridge that commoners would herd their cattle onto the marsh. Thus far from being an idyll, if I was here 200 years ago, this would still have been a site of regular pastoral toil: the working commons land as a free resource to enable ordinary people, commoners, to earn a livelihood through their own ways. As Peter Linebaugh says in The Magna Carta Manifesto the 'commons rights were entered into through labour'. It is still how we understand the commons to be in imagination, the Commons version 1.0, the common resource that is also the subject of constant revision in contemporary political discourse: Garrett Harding's Tragedy of the Commons, Elinor Ostrom's Governing The Commons, the commons of modern historians like Colin Ward and E.P. Thompson.

The institution of Lammas rights of access and time-sharing created a balance at multiple levels of the social, ecological and economic order with a distributed economy. This was the self-managed subsistence economy that maintained the Commons without depleting its resources, what E.P. Thompson described as the 'moral economy'. The moral economy was based on the commons of practice, on the realpolitics of the 'pure commons' of open Land as a common treasury.

But when the enclosures went so far as to adversely affect the lives of the new bourgeois living in congested over-polluted cities, self-interest naturally kicked in. Simon Fairlie's The Land describes how steps were then taken to preserve the remnants of Commons land with the Commons Preservation Act of 1876.

And so remaining Commons land, a million acres or so, came to stand for a markedly different purpose; no longer a space for the poor to earn a living as sought by the Diggers, but as a protected space for social recreation or enjoyment of nature: the Commons version 2.0

plantain flowers

plantain flowersSo just as Commons 1.0 as lammas land wasn’t pure unadulterated commons but rather a working mix, the publicly-owned commons land is also a composite bag of interests. Some sections of the marshland are owned by Hackney Council, some by Lee Valley, some by the Canal and River Trust and some by the National Grid - marked by their electricity pylons.

They all work together for the latter-day Commons 2.0. It's what I turn to as my place of retreat. As autumn arrives, like the commoners of past ages I forage for traditional plants with medical qualities to avoid winter colds - rosehip, mallow, horseradish, elderberry and so forth. The marsh is a hidden treasure trove of wonders for those willing to exercise the redundant forms of labour they demand.

rosehip

rosehipThere's room for all though it's really the playing fields, the sport rather than nature through which the marsh connects with the diversity of Hackney's inner-city neighbourhoods. But this is a world apart from the streets of Hackney. And our's is an age of upheaval in conflict with such a model of the public sphere.

In the global era, new forces are now battling to reshape the human subject and redefine our cities. Benjamin Barber describes them in a binary, the twin protagonists of McWorld and Jihad. McWorld drives society to open up to global perspectives and institutions, whilst Jihad, not specific to any religion, drives communities to revert into their own identities and groups; 'today the choices are secular universalism of the cosmopolitan market or the everyday particularism of the fractious tribe'. Nowhere is exempt from them.

blackberries

blackberriesProtected Commons land, as Commons 2.0 was never meant to be a part of this internecine civil war. It was created to use nature to segregate and separate the commons from urban life and all such strife. In its DNA Commons 2.0 is politically latent, just not cut out to confront the new realities. Instead it can only serve to shift the political process to the 'reverse gear' of a conservation or protectionist project. Thus its value as a site of new political antagonism is questionable. New political antagonism refers to processes that bring into shared experience new forms of political conflict that existing political institutions cannot accommodate; and whether these are politically regressive or politically progressive and how they key into contemporary social formations.

As the shape and nature of society has transformed around it, the Marshes functioned as a valued resource in historical stasis, a sanctioned space in a progressively unequal and divided social landscape. And the hard lesson from the Olympics is that today extrapolated realities, projected realities mean much more than lived realities. It's not because the present is unsustainable and therefore not of significance, but of 'who' and 'what' presents the greater project for the greater future.

If the Olympics experience has provoked the marshes as Commons 2.0 to an existential brink, the tragedy is that the driving forces of today's political, as Benjamin Barber names them, are destructive reactionary agents of change.

This is why a Commons vision becomes important: the return of the Commons as the new political, to break out of its enclosure as the working engine of a social order. Without this role shift, the driving binary would extrapolate the logic of the current economic regime to claim the Commons on our behalf and return it to us as consumers whilst the resisting imagination vainly reverts to modes of pre-modern social relations.

horseradish

horseradishThe return of the Commons as political form is the return of the Commons as a resource for the means of life. What it entails always involves a level of realpolitics, as political and economic practice. But it re-asks 2 questions:

1 what is the means of life in the global networked age.

2 who are the subjects of an equitable new global order

The subjects of this new order, are not just us as citizens or, us as we are today, but all who are a part of the moral economy the Commons implies - often what's outside the vision of the present order. To extrapolate the political potential in radical terms, this may be all forms of subjects, human and non-human, who cannot be commodified but reconnect through the Commons. Thus for example the things here like the horseradish, the hawthorn, the elderberry, the plantain on Hackney marsh, as much as the human labour of foraging for them. The Commons provides the space but without re-imagining the spectrum of life in the process, it cannot possibly restructure the relation between the social order and the natural order. The Commons has to ask who the Commons is for.

So if Commons 1.0 was for us as the peasant commoner, Commons 2.0 for the subject citizen of the Modern public sphere, the new Commons may yet be for something very different in nature – for both human and non-human.

If Commons 1.0 was the common treasury given to humans by nature, Commons 2.0 was a protected interregnum, the new Commons would now be a common treasury given by humans to nature; to which we can belong. It's somehow a part of the chain of historical role reversals the Commons narrative has involved over the centuries. This then would be the Commons 3.0.